The Origins of Ledger Art

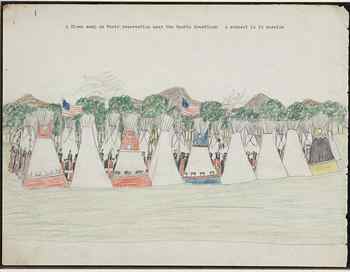

Plains Indians were known for their paintings, or narrative drawings, produced on paper or cloth. Usually, the medium was contingent upon whatever was handy. In the beginning, this would mean drawings and paintings were produced on animal skin.

Dakota man painting figures (winter count) on buffalo skin. 1929. Photo by J.A. Anderson. Source – National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

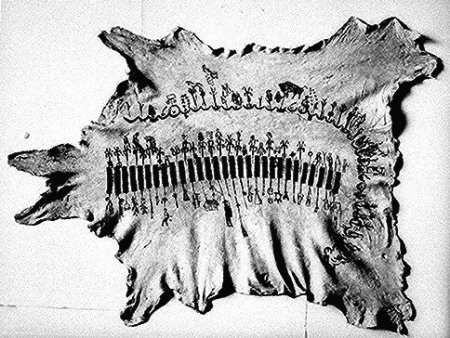

Calendar of 37 months, 1889-92, kept on a skin by Anko, ca. 1895

However, as the United States grew in size, old accounting ledger books, received from trade with government agencies and other sources, became a common source of material. Hence, the birth of ledger art.

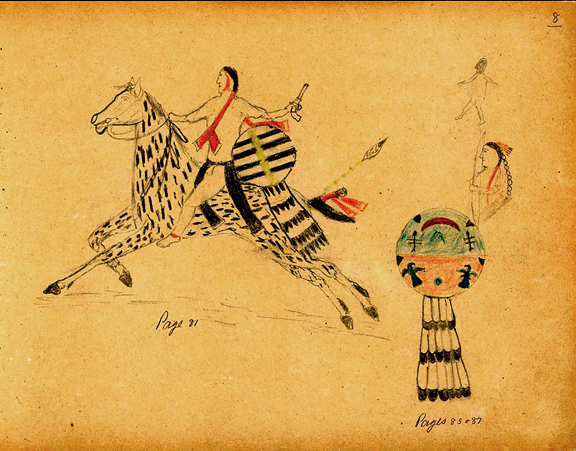

Along with these government agencies, missionaries, military presence, and traders, came fountain pens, pencils, watercolor paints, and crayons. This allowed the Indians to experiment a bit more, and also provided a greater bit of detail than earlier drawings. Earlier drawings tended to be stick like in nature, with any body fields completely colored in with solid coloring. Outlines were hard, and so were the narrative nature of the drawings. Typically, they depicted epic quests, or events that marked status for certain individuals. Later on, they would depict massacres, wars, and skirmishes between the Indians and military officers of the United States army.

Ledger Art was also the result of children’s doodles on recycled ledgers given to children in “Indian Schools,” and remain a tragic reminder of the crimes against them.

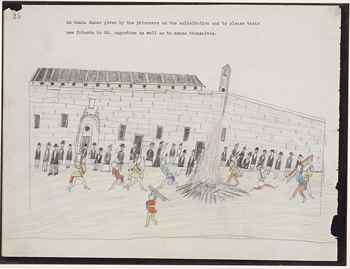

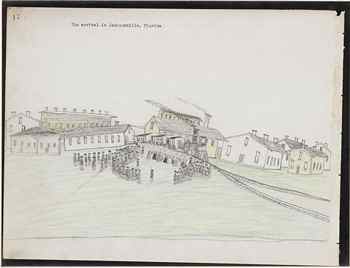

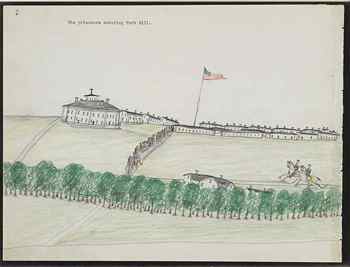

Perhaps the most noted ledger art, came from a group of prisoners held at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. These prisoners were captured as a part of the Red River War, also known as the Buffalo War.

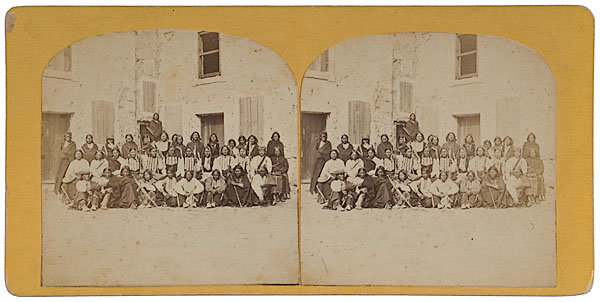

A stereoview lacking photographer’s mark, but attributed to O. Pierre Havens, Savannah, Georgia, identified in pencil on verso as Indians confined at Fort San Marco / St. Augustine – March 1876. Following the Red River War of 1874-75 and determined to prevent further trouble, the U.S. government sent 72 Indian prisoners to Fort Marion, or the Castillo de San Marcos as it is referred to here, in St. Augustine, Florida. The group included 33 Cheyenne, 27 Kiowa, 9 Comanche, 2 Arapaho, and 1 Caddo.

They consisted of several different Native American tribes including the Comanche, Arapaho, Kiowa, Cheyenne, and Caddo. The central issue at hand concerned the last free buffalo herd. The Indians fought to protect the herd and establish their independence. However, the U.S. Army was too much for them. The winter of 1874 was the most unfortunate event. It helped to finalize defeat for the Indians, as many of them were forced to surrender. Those prisoners of war were housed at Fort Marion for the next three years, beginning with the year 1875.

It was there that the commander of Fort Marion, Richard Henry Pat Pratt, decided this would be a chance to westernize the Indians a bit. He attempted to give them a formal education. With that education came basic art supplies. The rest, as they say, is history. Twenty six of those prisoners at Fort Marion produce some of the most prolific works of ledger art that we have on hand today.

Everything from battle exploits to courtship served as subject material.

The really unique thing about their ledger art is that you see the story of expansion and advance unfold. You just have to know what to look for. Certain pieces feature items such as cameras and trains. These would later become items that were used as a foundational force, to shape and document our expansion and history. However, at the time, they were included because they were new gadgets.

Though the works were popular during the late 1800s, it would not be until the year 1928 that ledger art was recognized as it’s own form. It seems that a few of the Native Americans held to the craft, and turned them into professional careers. Of note are ledger artists Carl Sweezy, and Haungooah.

Drawing by Carl Sweezy, 1904

Detail of ledger painting on muslin by Silver Horn (Haungooah), ca. 1880

Carl is a descendant of the Arapaho tribe, and Haungooah is part of the Kiowa tribe. Not only did they become professional ledger artists, but they went on to inspire a group of ledger artists known as the Kiowa 5. When their work was displayed at the International Art Congress in Prague, Czechoslovakia in 1928, it was met with instant success and applause. Ledger art had inadvertently transitioned from being a primitive cultural expression, to a full blown style of artistry… in about 50 years.

©2015 Great River Arts

No comments yet.