14,000 By Jack Nisbet

This past winter the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture in Spokane hosted a travelling mammoth and mastodon exhibit called “Titans of the Ice Age”. The remarkable show, originated by Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, combines gigantic bones and skull from five continents with life-size modern restorations, dioramas of past habitats, video clips of excavations, interactive tusk-fighting games, recorded trumpet blasts, comparative data on Columbia and woolly mammoths, mastodons and modern elephants, and skulls from a host of Pleistocene megafauna, including a 10-foot tall cave bear that greets museum-goers at the exhibit entrance.

The curator of the original Field Museum exhibit was Daniel Fisher, a paleontologist from the University of Michigan who has pioneered new ways to explore the details of the Ice Age world. In April, when Fisher journeyed to Spokane for a series of lectures in connection with the exhibit, he allowed himself to be lured into a field trip that visited one of our own region’s significant mammoth sites; a small bog within the town of Latah, southeast of Spokane near the Idaho border.

In 1876 the Coplen brothers, while farming on their Latah farmstead, managed to excavate an array of large animal bones from a wet seep just above Hangman Creek. Led by brother Ben, they loaded the best of bones on a wagon and exhibited them from Colfax to Portland. Parts from at least four individual animals in their collection were then purchased by what became the Field Museum, freighted to Chicago, and assembled into North America’s first full mammoth mount. That mount known as the Hangman Creek or Latah mammoth, remains on display at the Field Museum to this day.

Dan Fisher works at the forefront of technical science, microscopically examining thin sections of ancient tusks to tease out details of single animal’s life history. He was part of the team that analyzed the Lyuba, a young Siberian Woolly mammoth that stands as one of the best preserved Ice-Age mammals ever studied. For the Titans of Ice Age exhibit, he oversaw a meticulous replica of Lyuba, accurate right down to the mold growing on her mummified hide. But as our tour bus climbed out of a Hangman Creek canyon on Valley Chapel Road and emerged into the rolling Palouse Hills, Fisher revealed that something much simpler first attracted him to the mammoth world.

Beginning soon after his arrival in Michigan in 1979, Fisher was called to several local sites where mastodon remains turned up during excavations of old farm ponds. As he studied one of those ponds in more detail, he slowly realized that four discrete piles of mastodon bones lay scattered within its perimeter. Careful examination of the recovered bones revealed marks of knapped stone knives on separated limb joints, and some of the larger bones appeared to have been smashed into smaller pieces with hammer stones. Aided by a cooperative farmer, Fisher found himself investigating not only ancient elephants, but also links between humans and the late Pleistocene megafaunal extinctions.

The farmer originally made fisher promise that he would complete any digging he had to do within 24 hours. But when the farmer saw that the mastodon bones that emerged from his familiar pond, he became totally engaged in a dig that eventually lasted for years. In time he donated the body of a workhorse that had died from natural causes so that Fisher could practice butchering and smashing its bones in ways that matched the mastodon remains. Fisher then wrapped the meat he obtained in hide packages and sank them in the pond with stones.

The water in many Michigan ponds is naturally rich with tannins, which cut down on bacterial growth. When Fisher discovered his meat masses a month later, he found that the main bacteria present were lactobacilli. The lactic acid they produced not only discouraged other bacteria from growing in the meat, but also over several months imparted a flavor and aroma that resembled an aged Stilton cheese. Even after six months of being anchored in the pond, the horsemeat remain palatable. “Yes”, said Fisher to the bus crowd. “I ate it on multiple occasions, and didn’t think it was bad at all.”

Lab work determined that the mastodon site dated back to around 15,000 years ago. That early date, combined with Fisher’s extensive lab work has allowed him to develop a theory of long term human interaction with Ice Age mammals such as mastodons and mammoths. He postulates that people lived alongside such mega fauna for thousands of years. They developed ways to hunt the animals and preserve their meat. Over many generations, some still to be determined combination of factors, probably including a growing human population and a warming climate, led to the extinction of Columbia mammoth, woolly mammoth and American mastodon.

With our bus load of people still trying to absorb Dr. Fisher’s theory, we coasted through Latah and crossed Hangman Creek so we could look back at the old Coplen homestead. The excitement of the brothers’ find has never entirely died down here.

In 1919, a dig sponsored by the Cheney Cowles Museum (now the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture) returned to Latah in search of material to create Spokane’s own replica mammoth. They found many shattered fragments of mammal bones, but nothing like what it would take to create a full mount.

In 1981, Eastern Washington University, dispatched a team to make a more complete scientific survey of the area. They charted the same soil layers and geology that Ben Coplen described before they were halted by bad weather and crowd management issues- just as in 1876, everybody wanted to come out and have a look.

The landowner and the backhoe operator from the 1981 attempt greeted our bus and talked to Dan Fisher in much the same way that the professor’s farm associates from Michigan had. They were curious about what lay hidden in their land, and what happened there in deep past. Both were eager to cooperate with scientists if the time was ever right to try again.

A convergence of information might make that happen. Even as the Titans of the Ice Age exhibit was on its way to Spokane, Archeological Historical Services of Eastern Washington University cut a sample wedge from one of the Latah mammoth ribs and send it off to a respected laboratory. The date came back, with only a small margin of uncertainty, at 14,00 years before the present. One of the most widely accepted recent archeological human dates, from a cave in eastern Oregon, also has been calculated at 14,000 years ago.

In our area, the most-often-asked archeological question is whether any humans were around to witness the Ice Age floods that poured out of Lake Pend Oreille that shaped the landscape around Spokane and the Columbia basin. Geologists constantly recalibrate the date of the most recent of that series of floods, but one date that comes up frequently is 14,000 years ago.

At the last stop of our field trip, we stood on Steptoe Butte and looked across the Palouse Hills north toward Spokane. From that viewpoint, on a breezy spring day, it was very hard not to visualize large bodies swinging their trunks steadily as they gathered herbaceous food along the endless lush slopes.

The next easy step was to think was that perhaps there were a few days, scattered over several thousand years, when some of the animals took time out of their busy feeding schedule to lift their heads at the sound of a wall of water thundering past some ways downstream. In time the noise receded, and the mammoths went back to feeding.

Then there would have been another day, much quieter, when tiny specks of new animals that walked on two legs came upon the scene and did not go away.

For more of the Fisher and his areas of study, including a National Geographic video about Lyuba, visit https://lsa.umich.edu/paleotology/research/daniel-fisher.html. More can be found by doing a video search for “Waking the Baby Mammoth National Geographic” and the article search for “U-M paleontologists unveil online showcase of 3-D fossil remains.

For more about the Ice Age exhibit, go to https://www.fieldmuseum.org/about/traveling-exhibitions/mammoths-and-mastodons-titans-ice-age.

For more about the Coplen brothers’ 1876 excavation and travels with the Latah mammoths, try the “Behemoth” chapter in Jack Nisbet’s Visible Bones.

http://reader.mediawiremobile.com/ncmonthly/issues/201404/viewer?page=11

Treasured Northwest writer Jack Nisbet is a teacher, naturalist, and writer who lives in Spokane, Washington with his wife and two children. http://www.jacknisbet.com/

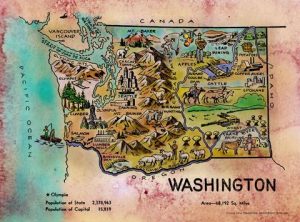

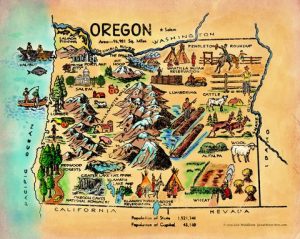

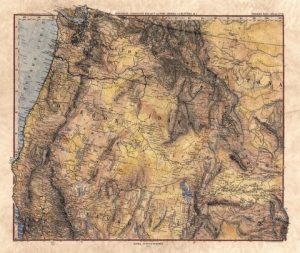

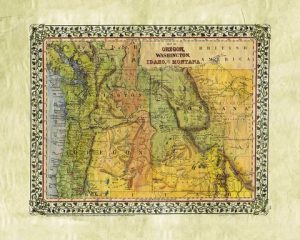

See our beautiful maps of the Great American Northwest!

Kid’s map of Washington https://great-river-arts.myshopify.com/products/kids-map-of-washington

Kid’s Map of Oregon! https://great-river-arts.myshopify.com/products/kids-map-of-oregon

Peterman Gotha Map of the Northwest https://great-river-arts.myshopify.com/products/gotha-northwest

No comments yet.