The Magnificent Bryozoan By Contributor Jack Nisbet

Cherished Northwest Author

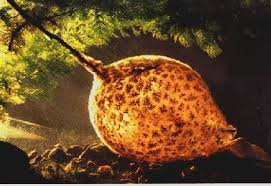

In September, a couple of friends went kayaking on Shepherd Lake, six miles south of Sandpoint. It’s a pretty little lake, a bit more than 10 acres in size, tucked into a classic rich Idaho Panhandle forest. The paddlers know the area well and were surprised to find that the water contained dozens of strange slimy blobs. The roughly round blobs ranged up to the size of classroom globes. Each one was anchored around a plant stem like a weaver’s spindle loaded with yarn. A striking pattern of star-like geometric figures covered each blob’s surface, and their consistency was like a Jell-O salad that broke off into chunks. When the husband plucked a blob up by its plant stem for a portrait, the soccer-ball shape slumped into something more like a football.

Back home, a quick check on the web revealed that the blobs were a bryozoan officially named Pectinatella magnifica, which means nothing more than “beautiful bryozoan.”

My friends mailed the curious photograph plus a brief version of their story to the Sandpoint newspaper. They also happened to send me a copy of the same picture, and I’ve been dreaming about geometric designs and gelatinous blobs ever since.

My initial thought was that the pattern on its surface looked a lot like a particular starry moss that thrives in the forest surrounding Shepherd Lake, so it made sense to learn that the Latin term “bryozoa” translates as “moss animals.” In fact, the bryozoan blobs in Shepherd Lake are made up of thousands upon thousands of individual creatures called zooids, each one less than a millimeter across, functioning together as a colonial unit. Although that description fits several exotic life forms, including slime molds and marine jellyfish, scientists place bryozoans in their own separate phylum within the animal kingdom.

The imprints of early moss animals show up in the fossil record about 500 million years before the present, at roughly the same time as the hard-shelled trilobites that distinguish several strata of our region’s rocks. Like trilobites, bryozoans spread across Earth’s oceans in a startling diversity of forms. Unlike the extinct trilobites, around 5,000 species of bryozoans still thrive on our planet today. Most species inhabit shallow coastal regions, but some have been found in the deepest ocean trenches, five miles below the surface. Most prefer warm water, but one remarkable member of the phylum drifts around the Antarctic ice pack. Most are rooted to the ocean floor or float at the whim of the current, but a few creep around on specially adapted individual zooids.

The individual zooids of all living bryozoa feed by extending crowns of fine hairy tentacles to capture particles of floating debris.

The species fall into three main categories.

Members of the first group develop calcified tubular skeletons. These forms encrust rocky surfaces, seashells and marine algae.

A second, more common group features cylindrical or flattened individual zooids. They use their calcified skeletons to create colonies up to several feet in size. Some of these look like coral or seaweed, growing in shapes that resemble wavy fabric, branching trees or finely tatted lace. Like the first tribe, members of this group live exclusively in salt water.

The blobs in Shepherd Lake belong to the third group. They live in freshwater and show no calcification at all. Instead, the tiny zooids transform bits of floating detritus into a gelatinous mass that binds them together – a habit that has inspired the common name “devil’s boogers.”

Many native shallow-water bryozoans perform important ecological work by stabilizing and binding free sediments in wetland environments. They can play a pivotal role in local food webs when they filter their sustenance from microorganisms, then make those nutrients available to fish and other vertebrates that prey on the bryozoa themselves.

The boogery blobs of Pectinatella magnifica can live only in warm water, and with the arrival of fall each gelatinous mass turns to mush. The only visible parts left behind are thousands of hardened masses of cells called statoblasts. Each small wheel shaped statoblast is rimmed with jagged hooks. They sink to the bottom of the lake and enter a period of dormancy that allows them to withstand drying and freezing. They wait.

In time one of those hooks can latch onto a passing muskrat, fish or duck’s foot that drags through the mud, and things begin to change. If a statoblast lands in a favorable situation by springtime, it can germinate asexually to form a new zooid. If there are others like it in the vicinity, they gather together to form a fresh blob on the water.

“Devil boogers” might sound like a joke, but bryozoans can be a nuisance. Over a hundred different marine species attach themselves to ship hulls, robbing the vessels of speed and power. Others have been known to foul pilings, piers and docks. Their freshwater counterparts can clog pump intake pipes and stormwater waste systems.

Moreover, with the help of humans, some of these ancient species are on the move. In North America, the Pectinatella magnifica was long considered native to warm still waters east of the Mississippi, but since 2000 it has been showing up more and more in the Pacific Northwest – first in west-side ponds around cities like Vancouver, Washington, then lately in lakes east of the Cascades. Many scientists believe this is a result of warming waters brought on by climate change, and that, once established, the beautiful bryozoan may find plenty of suitable habitat for expansion here.

Our region’s natural resource managers would like to learn more about the spread of these blobs, and the United States Geological Survey coordinates a Nonindigenous Aquatic Species database to track changes like this. If you know a lake where the blobs occur, or see one next summer while out on the water, you can go to the USGS fact sheet (https://nas.er.usgs. gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?Species ID=2335) and make a report by clicking on the tab at the upper right-hand corner.

Thanks to John and Laura Phillips for dredging all this up.

Spokane-based author Jack Nisbet’s favorite movie as a child was The Blob with Steve McQueen.

More of Jack’s books and lectures may be found at: http://www.jacknisbet.com/

This article originally appeared in North Columbia Monthly

http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/3e7a7b_07f57a2fbbf04dfb9762e65e187076d7.pdf

Pectinatella magnifica

Statoblast of Pectinatella magnifica

No comments yet.