Billy by Special Contributor Jack Nisbet

David Douglas was a Scottish naturalist who worked the Columbia country from the Rocky Mountains to the river’s mouth during three collecting trips between 1825 and 1833. Douglas also happened to be a dog lover and his relationship with various furry friends over those years reveals a lot about both the man himself and the way people related to domestic animals two centuries ago.

Dogs first appeared in Douglas’s writings only a few weeks after he left England on a voyage to New York City, in the summer of 1823. Douglas suffered with the crew for several weeks as the ship’s captain rationed drinking water during their overly calm Atlantic passage. When a bit of weather flew and it finally rained, the young naturalist “could not help but observe how dogs eagerly licked the decks”. He saw the world closely enough to understand that these ship dogs were just as thirsty as he was, and realized the relief it was for them to flop down on the deck to lick the much-needed fresh water.

Although Douglas made no mention about the breed, numbers or other behaviors of those deck-licking dogs, he soon discovered that their peers not only sailed aboard many ocean vessels of the time, but also milled around every native encampment and fur trade post in North America. In time he would learn to enjoy the “sweet music” of dogs barking as he closed in on any fur trade post, anywhere on the continent.

He also saw what they could do. When Douglas joined a horse-hunting expedition out of Fort Vancouver in the fall of 1825 with the Hudson’s Bay Company trader Alexander Mcleod, the trader’s bull terrier ran alongside them. The moment the party started a bobcat, Mcleod’s terrier leaped at the cat, caught it by the throat, and brought it down. Douglas expressed elation with both the action and the specimen- he was a man of his time, and his job was to collect the region’s flora and fauna for science.

McLeod was far from the only fur trader who kept dogs around. In summer 1826, Douglas met a company brigade that had just made a difficult portage around the Cascades of the Columbia- difficult because the tribal men who helped carry their gear had made off with several valuable articles, including traders John Work’s personal dog.

And at fort Walla Walla that same summer, when some thieving pack rats were keeping Douglas awake at night, he reached for his gun, “which, with my faithful dog, always is placed under my blanket at my side”, and blasted one to smithereens. This quote, which appeared in only one of Douglas’s three accounts of the incidents, included no further details about his canine friend.

But the naturalist obviously had a weakness for such companionship. In autumn 1826 he joined a fur trade excursion to Oregon’s Umpqua country, along both Mcleod and a hunter named Jean Baptiste Mckay. Apparently Mckay brought several dogs along, and when Douglas broke away from the larger party to return to Fort Vancouver, one of the animals tagged along.Douglas awoke the next morning to find the dog in “his accustomed place, asleep at my feet.” Like many a child who lets a stray follow them home, Douglas allowed Mckay’s dog to return north with him, explaining that he had no way of sending him back to his rightful owner.

Of course , having dogs around means more than a comfortable snuggle at night. In spring 1827, Douglas wrangled numerous collections up the Columbia for a passage across the Rockies to Hudson Bay. When his canoe brigade stopped at Fort Colville, he unpacked some of his most prized specimens to dry, including a pair of sage grouse skins that he had lugged hundreds of miles. Wary of the camp dogs, he wrapped the bird specimens in oilcloth and propped them up the tent poles.

When the mutts figured out a way to snag them anyway and tore them to pieces, the naturalist was “grieved beyond measures”.

Douglas left the Pacific Northwest for England in 1827, and during his two years there made a visit to his home village in Perthshire, Scotland. This may be where he picked up his personal pet named Billy, who joined him to his return voyage to the Columbia via Hawaii.

By the time Douglas arrived back at Fort Vancouver in 1830, he described Billy as “my faithful little Scotch terrier, the companion of all my journeys.” Billy was with Douglas when he ventured out of the fort after being laid low by a terrible malaria epidemic that summer; the two were greeted by horrific sight of “flocks of famished dogs howling above, while the dead bodies lie strewed in every direction on the sands of the river”.

Billy also accompanied his master to California for two more years of plant collecting in the Spanish ranchland, where one resident described Douglas as frequently setting off on his own, attended only by his little dog and a rifle in hand.

Douglas and Billy sailed from California to the island of Oahu, where they caught the Hudson’s Bay Company packet back to the Columbia for a third time around. From Fort Vancouver , in the spring of 1833, Douglas set off upstream again, this time with the goal of reaching the upper Fraser river and perhaps even the Russian post at Sitka, Alaska. Accompanying him was “my old terrier; a most faithful and now, to judge from his long grey beard, venerable friend, who has guarded me throughout all my journeys.

The pair traveled with a fur trade brigade as far as Fort St. James, above modern Prince George, British Columbia. When Douglas decided to turn rather than brave the overland slog to the coast, he and Billy ended up in a canoe that capsized in the Red Rocks Canyon of the Fraser. It’s a rough stretch to overboard, but both man and dog survived to continue downstream to Fort Vancouver.

Soon afterward, they sailed together for the big island of Hawaii. There Douglas carried on much as he had on the Columbia; befriending locals, collecting plants, observing native culture, climbing mountains in support of his new-found interest in surveying, and generally fooling around with his dog.

During one epic feast at a Hawaiian village, he described Billy as tussling with a pair of cats over some discarded fish entrails. The pair were looking for a ship home from Honolulu when Douglas ran into a Protestant missionary named John Diell, who convinced the naturalist to return to the Big Island for some more volcano climbing. On July 9, 1834, Douglas and Billy disembarked at Kohala Point, intending to walk overland to Hilo. There they would rendezvous with Diell and a climbing party to ascend Mauna Kea.

Five days later, Diell was in Hilo as planned, when a Hawaiian man rushed up to the house where he was staying to announce that Mr. Douglas had fallen into a cattle pit trap and been trampled to death by a bull. It was a complicated story told mainly by a British-Australian bullock hide skinner named Ned Gurney.

Some local people thought that either Gurney or some disrespected native Hawaiians might well have murdered Douglas and dumped him into the pit. An investigation cleared Gurney of any wrong doing, but rumours have persisted, and to this day there are people on the island who believe that foul play was involved.

But one detail of Ned Gurney’s story stands out. He testified that after hearing news of Douglas’s situation from two Hawaiian men, he rushed up a trail to three pit traps that he had dug himself. It had rained the previous day, and cleared footprints around the site showed Douglas examining each of the three pits, then moving a few steps up the trail before stopping to backtrack for one more peek at the captured bull. It was there that he slipped and fell into the pit.

At the spot where he turned around, Douglas left the faithful Billy to guard his pack full of surveying instruments. When Gurney came forward and discovered the cache, Billy was still sitting calmly.beside the rucksack. Gurney not only delivered Douglas’s body to the missionaries for an inquest, but also presented them with the kit of instrument and the grizzled Scotch terrier.

Stories about the black deeds of Ned Gurney raise two question for many dog owners today; why would Billy sit quietly while somebody did violence to his most trusted companion? And why would Billy then allow Gurney to deliver him all the way to Hilo without a fuss?

No one has an answer to either question. The only certain fact about the case was that Billy was shipped back to London along with Douglas’s kit of surveying instruments. There he was adopted by a clerk in the British Foreign Office and lived out his life as a minor celebrity: David Douglas’s terrier Billy, who survived the Doctor’s pit.

Originally published in http://www.ncmonthly.com/

Treasured Northwest writer Jack Nisbet is a teacher, naturalist, and writer who lives in Spokane, Washington with his wife and two children. http://www.jacknisbet.com/

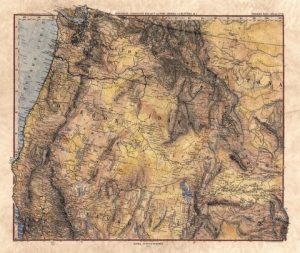

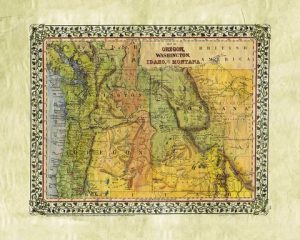

See our beautiful maps of the Great American Northwest!

Kid’s map of Washington https://great-river-arts.myshopify.com/products/kids-map-of-washington

Kid’s Map of Oregon! https://great-river-arts.myshopify.com/products/kids-map-of-oregon

Peterman Gotha Map of the Northwest https://great-river-arts.myshopify.com/products/gotha-northwest

No comments yet.